fine-tuned llm as program writers

A program-writer is a conduit between specifications and programs. In this post, we will explain how large language models (llm) can be an universal program-writer for different domains.

a menagerie of synthesizers

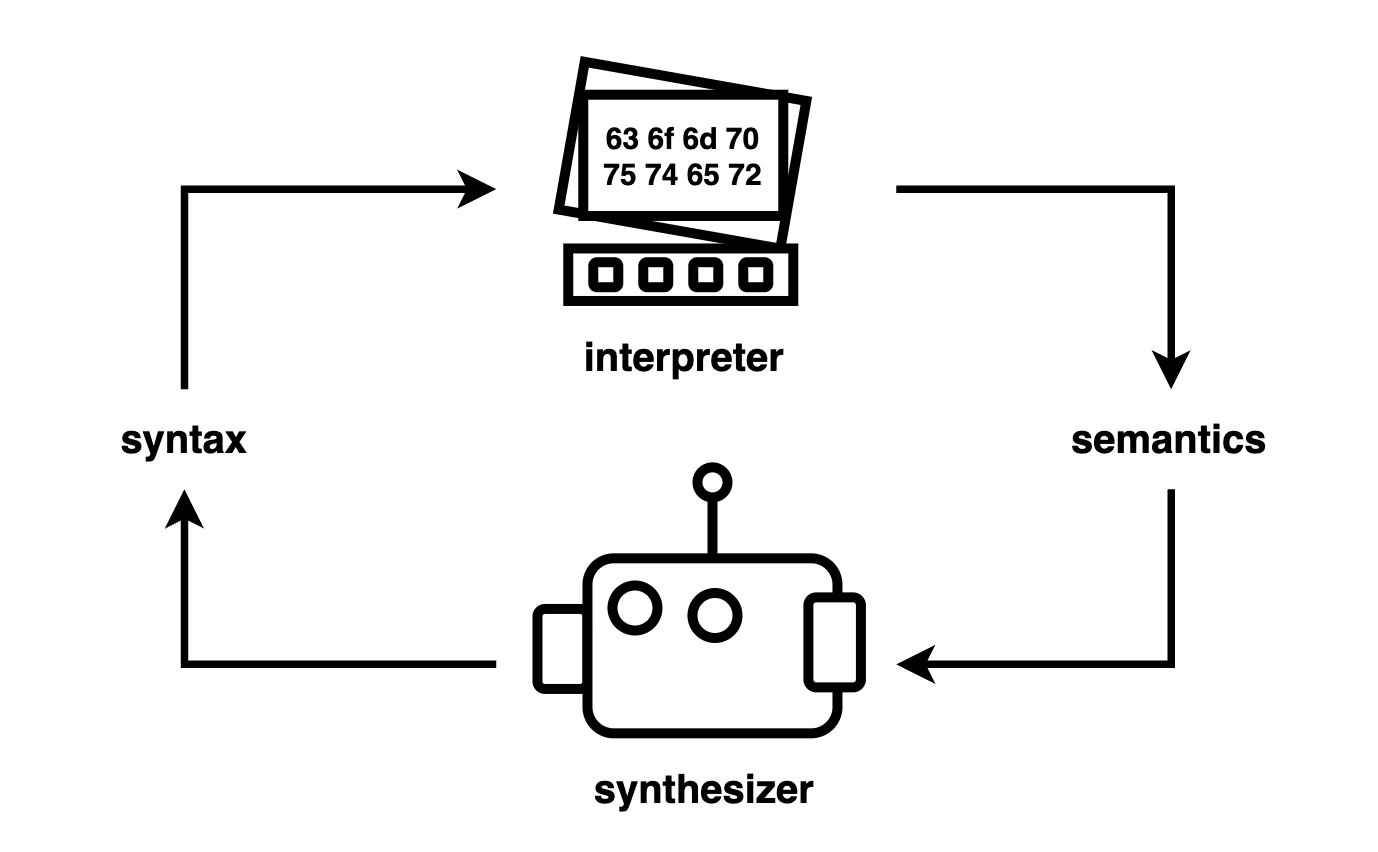

The synthesizer has a difficult job. It takes in semantics – what the program should do, and produces syntax – how the program should look1. Synthesis is running an interpreter backwards.

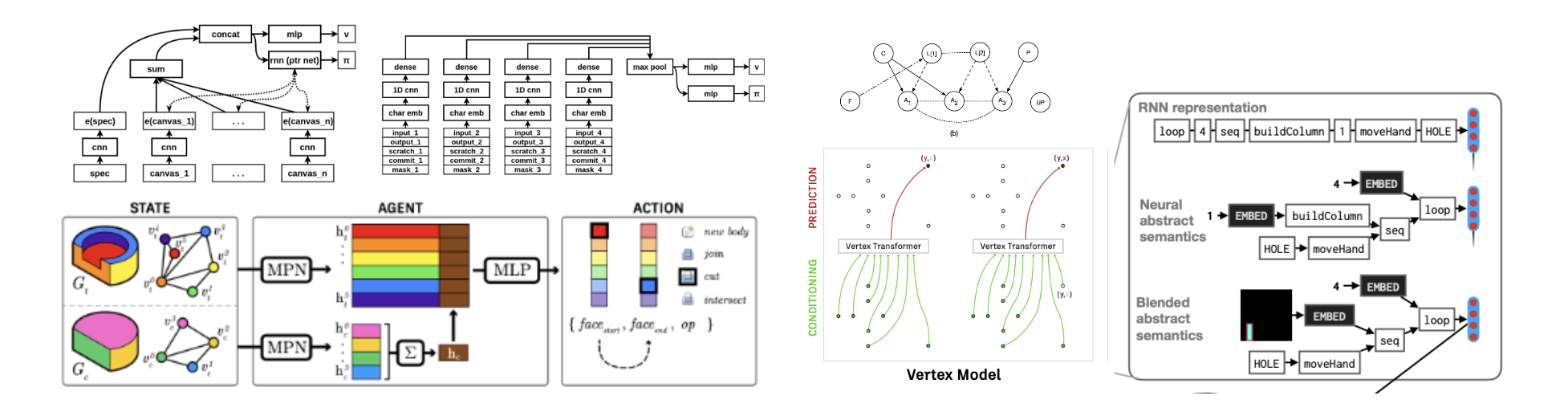

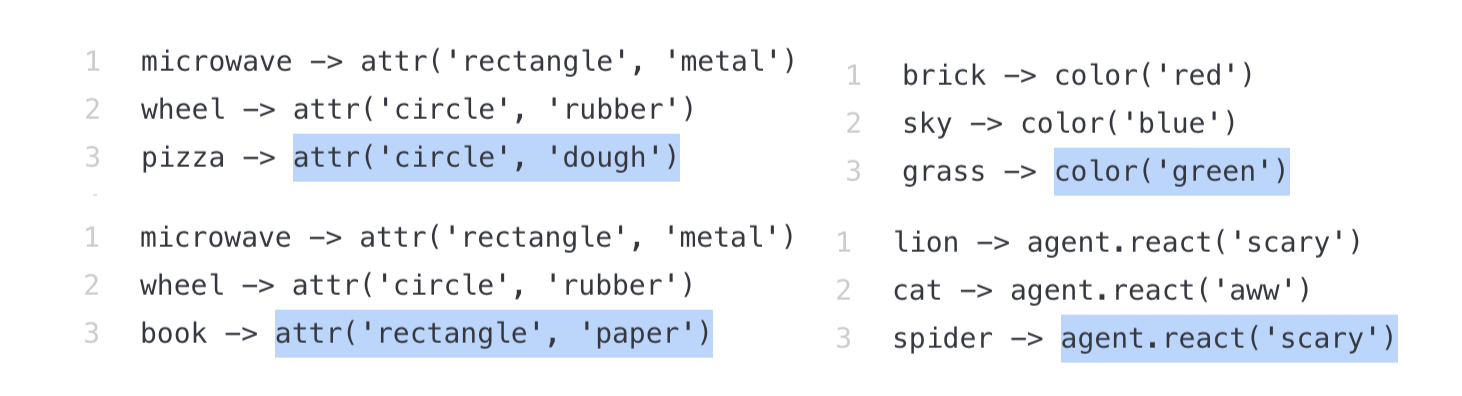

Given this hard problem, it seems reasonable that for every problem domain there needs to be a domain-specific synthesizer tailored to it. This has indeed been the case. Here’s a collection of program-writer architectures in some of my works.

While they look cool, significant manual engineering efforts and domain expertise were required to ensure that:

- the tasks from a domain can be concisely expressed in the programming DSL

- the synthesizer can reliably interpret the specification in its given form

- the synthesizer can reliably generate legal programs in the DSL

- the synthesizer can actually learn the structure of the meaning matrix M through training

This results in a messy co-evolution of DSL, interpreter, specification, and synthesizer – as the program-writer architecture is highly coupled with the specification language and the DSL.

large language models

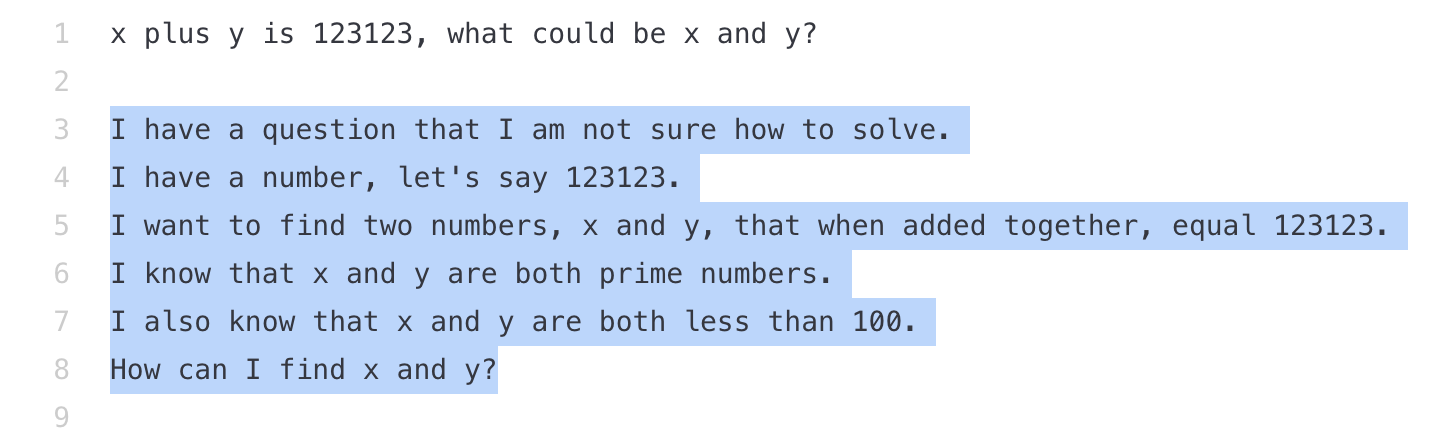

A large language model (llm) gives a distribution over strings (which can be) conditioned on a prefix string. Trained on an enormous amount of textual data, it can make some pretty surprising conditional generations. Below is an example from the openai-codex model: prompted with a textual input, it generates a likely string completion as output (shown in blue highlight).

The capabilities and limitations of llm are (as of 2022-aug) still being investigated. As I am learning about it myself, I encourage you to become familiar with them2.

llm for synthesis ?

These are my own assessments on why llm are useful for program synthesis. To make my case, I will show some interactions through prompting with the openai-codex model.

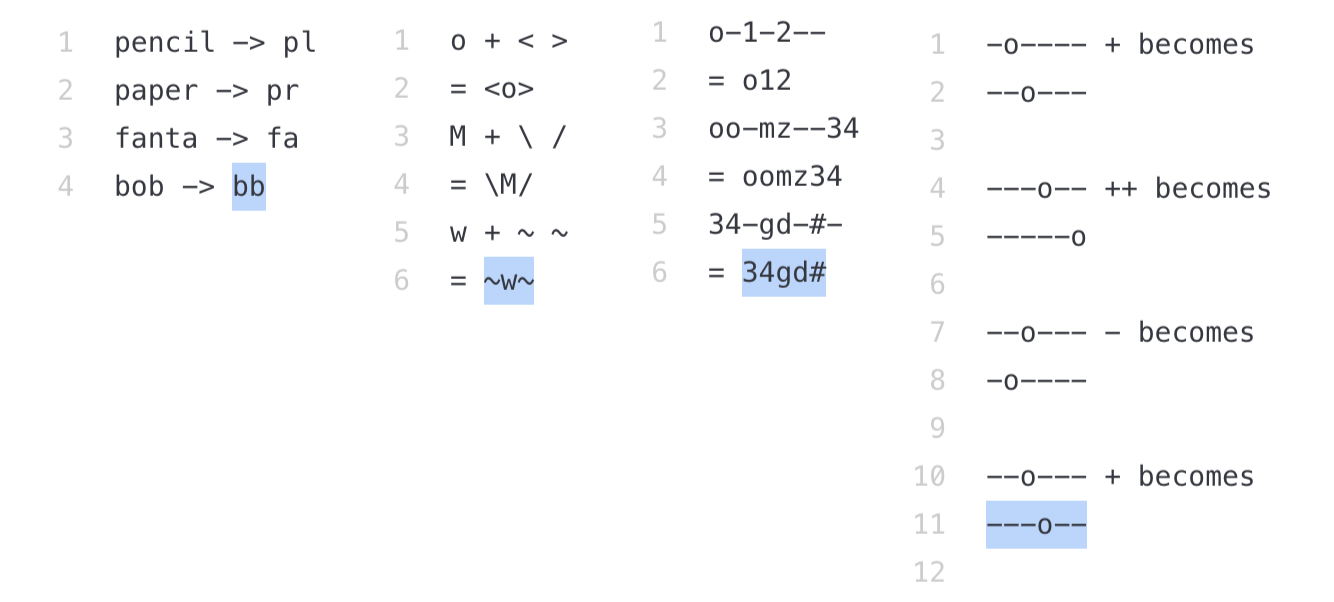

llm can pick-up programmatic patterns

Programs are stylized, patterned texts with distinct rules governing its generation and interpretation. It seems llm are predisposed to pick up these programmatic patterns.

llm has basic conventional knowledge of human language

llm has some knowledge of human conventions, expressed in large volumes of internet text.

llm are reliable in generating syntactically complex programs

Practitioners of program synthesis have avoided free-form text generation, as they’re rarely coherent. However, llm are very good at generating stylistically consistent texts3.

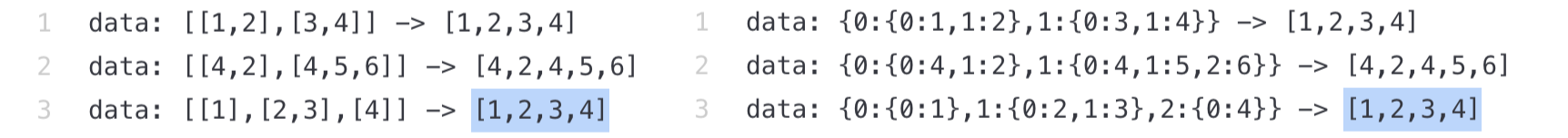

llm operates over text – a universal datatype

The specifications and programs are often easily represented as structured texts, this allow you to easily integrate program synthesis with an existing programming system, or iterate through different DSLs and specification languages – no parser required.

where prompting falls short

For our rectangle example, prompting cannot be used to generate a valid rectangle for the spec. In fact, llm+prompting fails very often for the specific problems we want to solve out of the box – the llm is trained on internet text data that are too different from our task.

For more complex tasks, we turn to fine-tuning, which supplies the llm with in-domain data.

Let’s take a break and vibe out. We’ll be fine-tuning for real next.

fine-tuning large language models for synthesis

When one fine-tunes a model, they take an existing model with reasonable weights, and continue to train it on a specific dataset. In synthesis, we take a llm trained on English and Python, and continue to train it on D – a sample of the meaning matrix M of our (rectangle) domain.

the model and the tokenizer

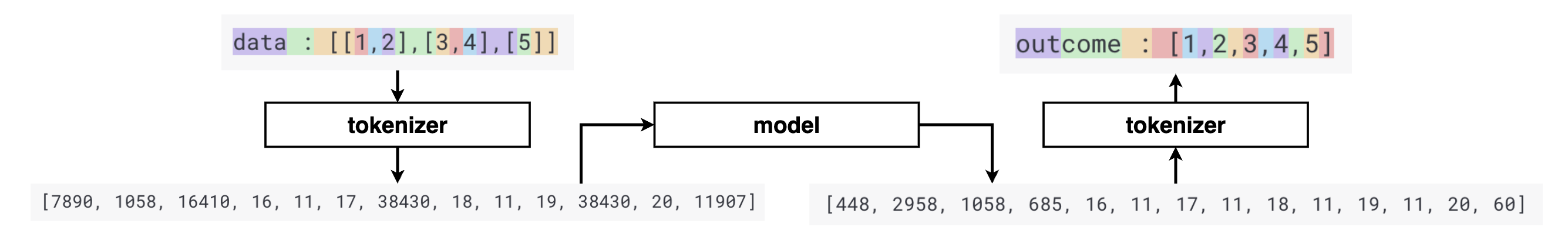

The model only operates over sequences of ids, and relies the tokenizer to translate between strings and ids. Here is how the codex model turns a string into a sequence of token-ids:

We’ll fine-tune the light-weight byt5-base model (2.17Gb). It treats each character (such as a or ]) as its own token (total 256 token-ids). One does not need a “truly large” model, since we’ll be giving it on plenty of in-domain datapoints. Getting the model and the tokenizer is fairly easy.

!pip install transformers datasets

from transformers import T5ForConditionalGeneration, AutoTokenizer, TrainingArguments

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained('google/byt5-base')

model = T5ForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained('google/byt5-base')data

We’ll be using the same kind of dataset D as the previous post.

# upload the following 2 files onto the colab vm instance

from rectangle import *

from rectangle_lm import *

import random

D_train = sample_D(5000)

D_test = sample_D(1000)encoding the spec and prog

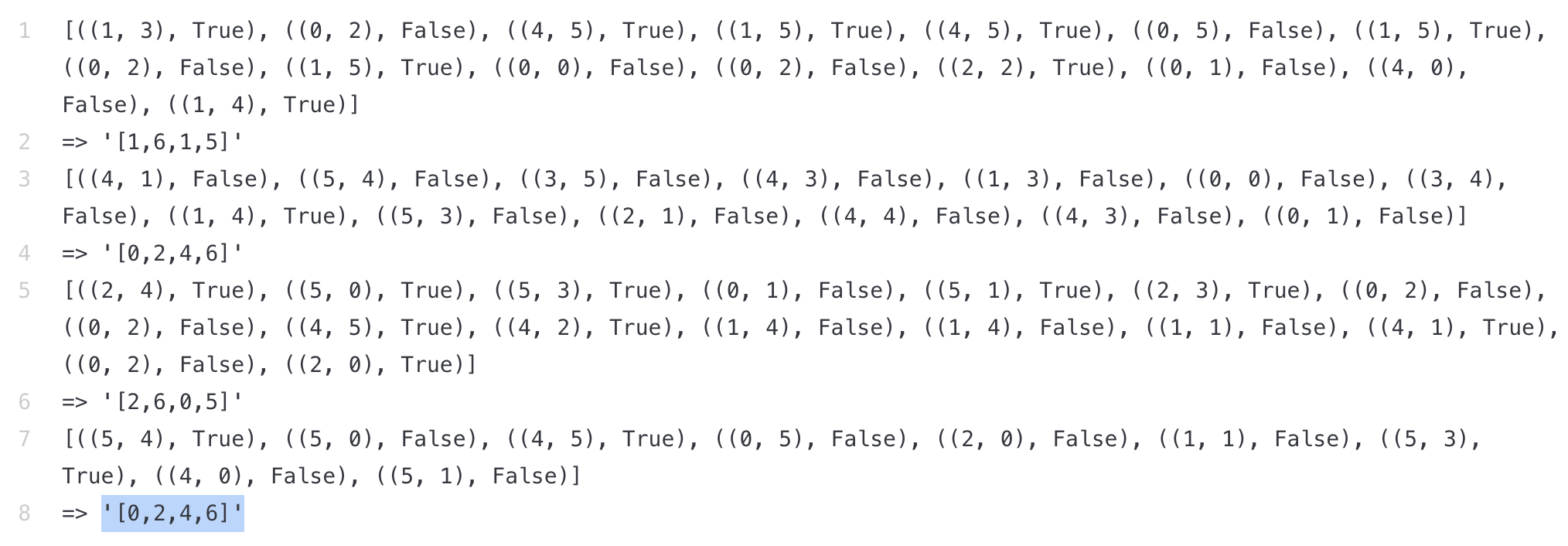

Encoding requires creativity – you want to accentuate the information for the model to make the correct decision. The run-time of the transformer algorithm is O(n^2), which is sensitive to the length of the strings. Thus, I simply try to minimize the length of the spec represenation.

Do keep in mind that re-naming the tokens comes at a cost of how the model can interpret natural language – for instance, if you rename ‘blue’ as ‘+’. This is usually fine if you have enough fine-tuning examples (for program synthesis, we can usually generate as many (prog,spec) pairs as we want).

def spec_to_str(spec):

return repr(spec).replace('True','+').replace('False','-').replace(')','').replace('(','').replace(' ','').replace(',','')

# before, length 261

[((1, 1), True), ((5, 0), False), ((3, 4), True), ((4, 5), False), ((0, 4), True), ((2, 3), True), ((3, 3), True), ((4, 5), False), ((0, 3), True), ((4, 3), True), ((0, 0), True), ((5, 2), False), ((4, 1), True), ((1, 2), True), ((5, 5), False), ((0, 3), True)]

# after, length 50

[11+50-34+45-04+23+33+45-03+43+00+52-41+12+55-03+]minibatch to tensor with collator

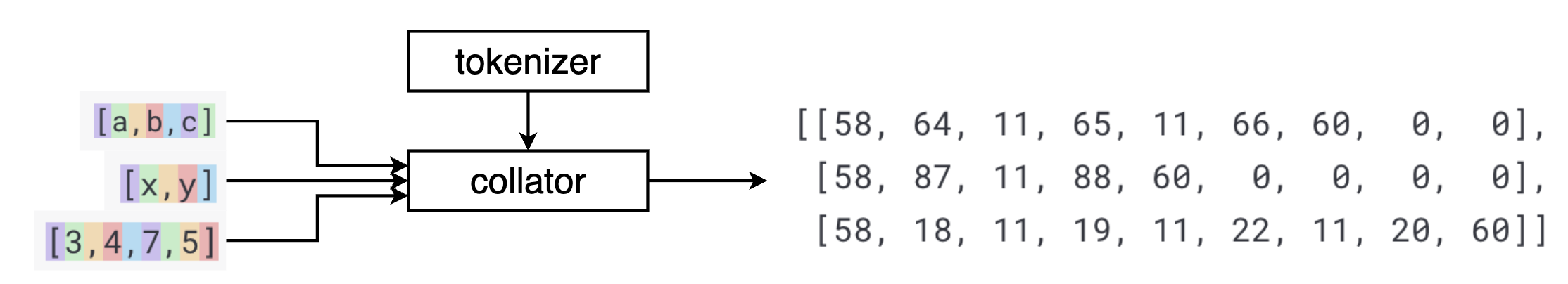

The collator takes a batch of input-outputs of different lengths and pad it into nice “rectangular” tensors that can be fed into the model for training.

This is what it looks like in code:

class Collator:

def __init__(self, tokenizer):

self.tokenizer = tokenizer

def __call__(self, batch):

# entry[1] is the spec, need to call repr to turn it into a string. entry[0] is the prog_str already

ret = {"input_ids": self.tokenizer([spec_to_str(entry[1]) for entry in batch], padding=True, return_tensors='pt').input_ids,

"labels": self.tokenizer([entry[0] for entry in batch], padding=True, return_tensors='pt').input_ids}

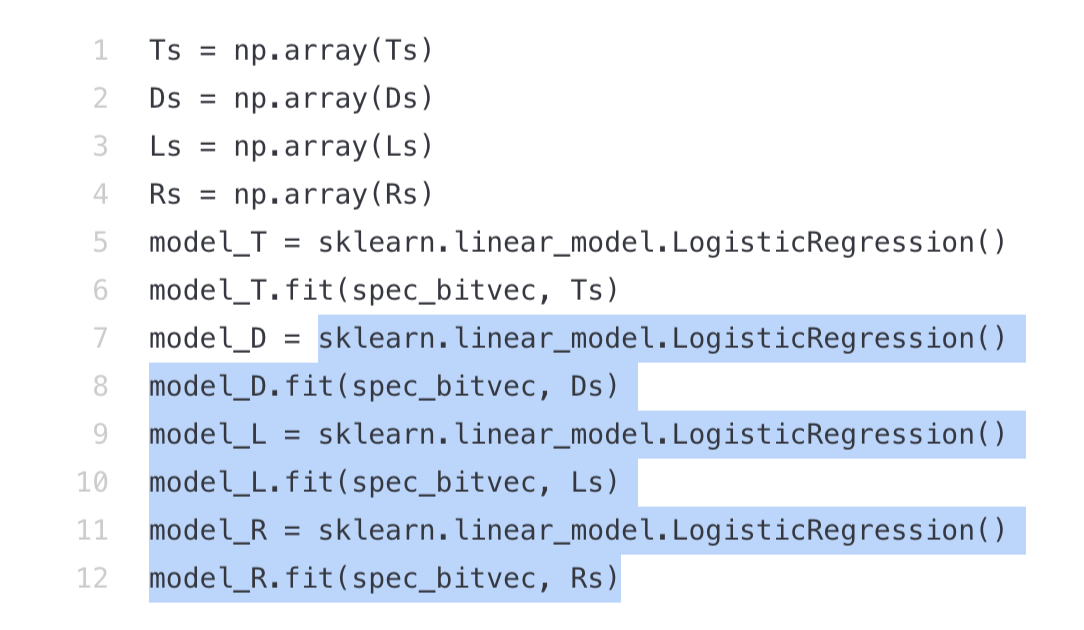

return rettraining, and interpreting the training loss

Training with the huggingface API is quite simple, simply call the Seq2Seq trainer class.

trainer = Seq2SeqTrainer(model=model,args = training_args,train_dataset=dataset,eval_dataset=None,tokenizer=tokenizer,compute_metrics=None,data_collator=Collator(tokenizer))

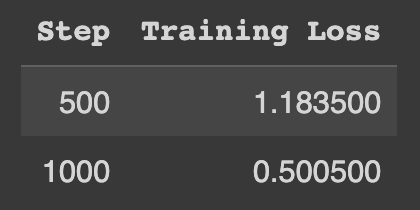

trainer.train()As the model is training, you will see the loss

The loss tells us how closely does the model’s distribution match the training data, smaller loss means closer match. Quantitatively, the loss can be interpreted as a per-token-perplexity, we’ll explain this with an example.

Let’s say we have a training data-point ("11+33+04-41-","[1,3,1,4]"), and it has a loss of 1.18 at iteration-500. It means that given the input "11+33+04-41-", on average, each token in [1,3,1,4] has a perplexity of e^1.18 = 3.25, or a 1 in 3.25 chance of being correctly generated. As [1,3,1,4] has a total of 9 tokens, and our model generates it 1 token at a time, the entire sequence has a 1 / 3.25^9 = 1 / 40453 chance of being correctly generated by our model.

At iteration-1000 we have a loss of 0.5, or a token-perplexity of e^0.5 = 1.64. Thus, the model has a 1 / 1.64^9 = 1 / 86 chance of generating the entire correct sequence. However, given a spec, there may be multiple satisfying programs, and the “1 in 86 chance” only speaks of a particular program, [1,3,1,4]. The model may very well find a different program that is also correct, making 1 / 86 a lower bound.

inference

After training (fine-tuning) on D, we can sample a few program-strings from specification – these are the candidates for rejection sampling down the line. The key parameter to sampling is temperature, a temperature of 1.0 is typically good – if you trust your model has fully learned the ground-truth distribution, a temperature of 1.0 is exactly it. A too-low temperature will ruin diversity, a too-high temperature will be too chaotic.

def generate_samples_with_temp(txt, n_samples, temp):

to_tokenizer = [txt for i in range(n_samples)]

outputs = model.generate(tokenizer(to_tokenizer, return_tensors='pt', padding=True).input_ids.to('cuda'), do_sample=True, max_length=128, temperature = temp)

results = tokenizer.batch_decode(outputs, skip_special_tokens=True)

return results

generate_samples_with_temp(repr(D_test[0][1]), 5, 1.0)

# ['[4,6,1,6]', '[1,5,3,5]', '[2,3,4,6]','[4,5,0,2]','[1,4,4,5]']

generate_samples_with_temp(repr(D_test[0][1]), 5, 3.0)

# ['[Tb2,2,6}', 'ee[>1,6,265,741F4]', '[0o9ѕdr_a|4,80,7]6ٓ5]і-$4732"r-H,', '[2˴в[4,4,3', '[A518,2/8žrev0B;D']This result is quite incredible, after fine-tuning, a llm that in theory can generate any string, is quite confidently generating correct looking programs/rectangles.

making a synthesizer with fine-tuned llm

We simply integrate the llm_writer into the synthesizer. As during training we have roughly 1 in 86 chance to recover the correct program (this being a lower bound), then a search budget of 20 is reasonable. As of today, inference from llm is still relatively slow compared to the tens of thousands of samples typically required for a SOTA program synthesizer, but I don’t think this will be a problem few years down the road – we just wait.

def llm_writer(spec):

# in practice please batch this instead of 1 at a time lol

return generate_samples_with_temp(spec_to_str(spec), 1, 1.0)[0]

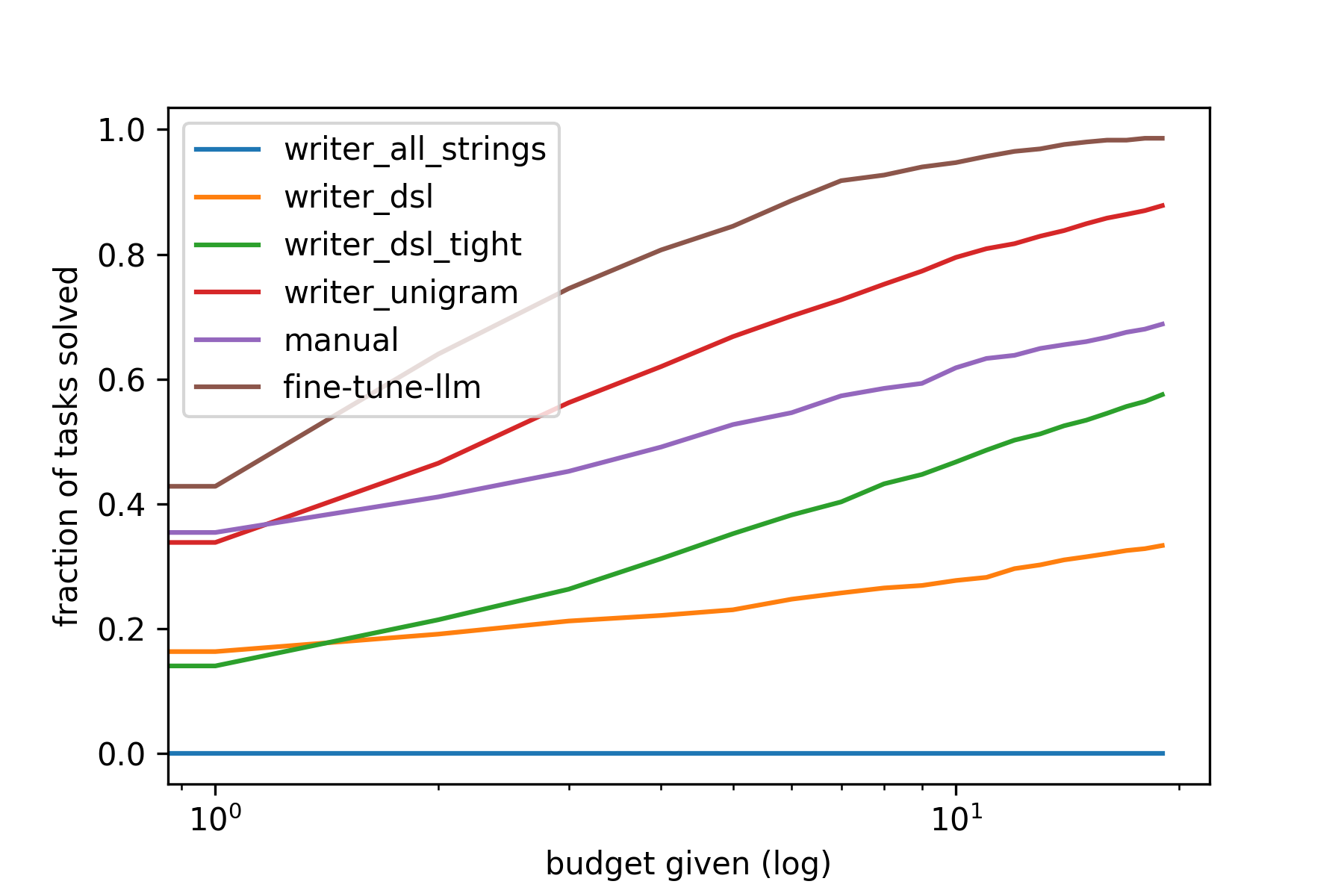

synthesizer6 = get_synthesizer(llm_writer, is_correct, 20)results

As we can see, by simply manipulating some strings, we were able to beat the other baselines in performance. Since llm are fully expressive, it does not have the issue of under-fitting (unlike the unigram-writer) and continued training will only increase performance.

code

All colab notebook of this post can be found here

It requires rectangle.py and rectangle_lm.py which were defined in previous posts.

exercise

Use different sampling methods such as top-p sampling or beam-search to take samples from our fine-tuned llm using this guide for reference. Which sampling algorith is more efficient given different search budgets?

conclusion future works

This concludes my 3 part series, I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I had fun writing it. Most importantly, I hope you are comfortable starting a program synthesis project.

I will post more synthesis topics as they become “mature enough” for a succinct blog post. I’ll be announcing these updates on my twitter (gimme a follow!)4. You can suggest new topics for me to write about, and please let me know if I was mistaken or unclear in my writings.

– evan 2022-08-31

notes

-

The gap between syntax and semantics motivated some of our works on execution-guided synthesis such as this and this. ↩

-

CS324, a stanford course on understanding and developing large language models ↩

-

follow my twitter for more program synthesis contents. Also, feel free to DM me with anything program synthesis related. ↩